SOLVITUR AMBULAND0 by Richard Frazer

Posted 2 weeks ago by John

SOLVITUR AMBULAND0

by

Richard Frazer

the act of journeying, and meeting the stranger along the way can be a subversive, even revolutionary act

the act of journeying, and meeting the stranger along the way can be a subversive, even revolutionary act

Solvitur Ambulando – It is solved by walking.

This phrase is attributed to a range of sources from Diogenes the Cynic to St Augustine. On first hearing it from the lips Patrick Leigh-Fermor, the restless and itinerant travel writer Bruce Chatwin was captivated. He knew, as thousands of others have known, that his brain only began to work fruitfully when his feet were engaged. Not only is walking our natural human state, when the path is broad enough and two people can walk side-by-side and communicate easily, so much can be resolved.

In addition, for Chatwin, the fact that babies tend to settle more readily when they are pushed around in a buggy is testimony to the reality that the human family is attuned to being on the move. After all, in a matter of a few thousand years, homo sapiens emerged out of Africa and peopled the world at an average pace of three miles an hour. That must have taken a fair deal of regular journeying! We are nomadic people and have been on the move with our tents as hunter gatherers for more of human history than we have been settled in our houses in cities and villages.

Coming as I do from the Christian tradition, I have always been struck by a remarkable irony. The name often given to members of the New Testament Church, was that they were the “People of the Way”, a journeying people, travelling folk. Why then, did these Christians soon begin to build huge edifices, such as the great cathedrals of Europe that exude an aura of fixity and permanence? Why, too, did the church at its various councils settle on an immovable set of doctrines and practices, when surely, journeying people knew in their hearts that being on the move deepened faith and understanding through the surprise of encountering the new, the different and the challenging? Some say it was because the early church, with the acceptance of Christianity by Constantine the Great, adopted the clothes of Empire, established its citadels of power and abandoned its travelling ways, and, some might say, its progressive journey towards newness and fresh understanding.

Admittedly, Christianity soon embraced the idea of pilgrimage and numerous holy destinations became places that people would travel to. But I think that one of the great insights that pilgrims gain and that those with power in the institutional church sometimes miss, is the fact that pilgrims, who journey with an open and hospitable heart, discover that the act of journeying, and meeting the stranger along the way can be a subversive, even revolutionary act in which new insights upset settled assumptions and ideologies. Both Luther and Calvin opposed pilgrimage partly, I am sure, because it proved hard to exert control over itinerant minds.

Home, it turns out, is not the destination with the great cathedral and the relics of a long dead saint to venerate, home is the journey. As anyone who reads the Canterbury Tales will realise, the only mention of Canterbury is in the title of Chaucer’s book, all the meaningful action is what happens along the way. It is the act of conversation on the journey, the surprise of hearing fresh perspectives from people from far away places, the conviviality of the evening hostelry where weary limbs are lubricated by story-telling and alcohol, that is where the problems of life and the “weight of existence” can be supported by the feet and by the freshly made friendship. That is also the place where the wind of the spirit, at loose in the world, can touch us, unfettered by the constraints and dogmatic limits of institutional life. The bishop, minister, cardinal, vicar, whatever ecclesiastical official you choose, cannot easily preach a sermon (and thereby exert mind control?) over the babble of pilgrim groups deep in conversation along the way.

And, other opportunities arise for those who “saunter” and converse as they go.

It is not necessary to walk only with old friends. It is possible, especially today on one of the growing network of pilgrim routes that criss-cross Europe, to meet new people and make new friends, on the hoof, as it were. And, one of the joys of this is that, unlike at home, where we see our neighbour day in day out, we might make a pilgrim friend for a day and never see her again. So, there is the immense freedom of personal disclosure, knowing that the things you say will not be held against you. Isn’t that why we sometimes find that there are people we live beside whom we have never really got to know, never really had a proper conversation with? We sometimes don’t want people to know too much about us in case they use the information against us.

There’s another opportunity for the walker too, a conversation with the landscape. John Muir hated the notion of hiking. It felt to him too aggressive a word. It has the quality of overmastering about it. Instead, he preferred that people should “saunter” in wild places, so that it is not just the companions (or bread sharers) who teach us new and revolutionary thoughts, but the landscape too.

It can read us and tell us its own stories if only we listen and become one with it, rather than seeking always to objectify it. Muir thought that the word saunter derived from pilgrims on their way to “Sancte Terre”, the “Holy Land”, to Jerusalem. “Where are you heading”, someone might ask a passing wayfarer. “A la Sancte Terre”, they would reply, to the Holy Land.

A Scottish friend who has lived in France for more than 30 years objects to this definition and suggests those who sauntered in France were landless peasants, displaced from their farms by rapacious landlords. They were “Sans Terre”. I like that juxtaposition and either definition will do for the one who saunters. The pilgrimage is something people set out to do, but it actually does us and even those without any faith background can feel the grain of their minds being changed by the conversations and insights gained along the way.

Getting out into the green, anticipating the gifts that come from the conversation and kindness of the empty handed stranger, becoming one with nature by walking through a landscape and allowing it to interrogate us, engaging in open hearted dialogue along the way, such things may just save civilisation and transform our relationship with the planet and one another. Maybe journeying is our natural state. Solvitur Ambulando!

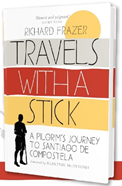

Richard Frazer – author of Travels with a Stick, published by Birlinn – April 2019